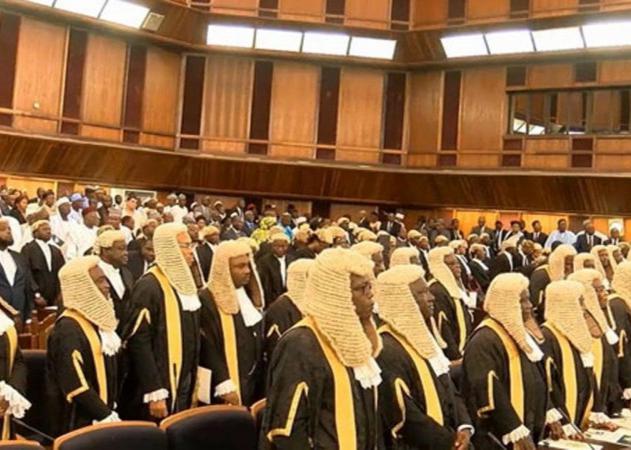

Of all its national symbols, the Nigeria Coat of Arms and its national anthem stand out for their representation of a national dream of peace, faith and development as well as the promotion of justice to make this dream feasible. Interestingly, without justice, it is highly impossible to realise peace, not in the least to keep such peace. Besides the ubiquitous presence of the Nigerian military who work to safeguard the national integrity of the nation, the presence of lawyers, judges and other allied practitioners in the legal profession often embodies an ideal of social equity, a social world in which no one is less than another because justice is real enough to establish peace in the land.

‘The judicial powers of the Federation shall be vested in the courts…’ and ‘The judicial powers of a State shall be vested in the courts…,’ states the Nigerian constitution. Also, ‘… the exercise of legislative powers by the National Assembly or by a House of Assembly shall be subject to the jurisdiction of courts of law and of judicial tribunals established by law, and accordingly, the National Assembly or a House of Assembly shall not enact any law, that ousts or purports to oust the jurisdiction of a court of law or of a judicial tribunal established by law.’ That is how greatly important the judicial arm of government is in Nigeria, like many other countries.

Like a bride-in-chamber chanced upon momentarily by her yearning groom, lawyers and judges are also endeared to many Nigerian citizens because they occupy a beautiful place in their social psyche. Having occasional opportunities to watch Nigerian lawyers posit and pontificate on arrays of matters of national, sectional and private interests more than often gives a good impression of hope for such a time that the almost defenseless citizen will be equal before the Law because they have professional lawyers to defend them before judges who themselves are also ethical in their duty enough to recognise the appellant or defendant to whom justice is due in any judicial circumstance.

Read Also: An Antithesis of Justice

But this was a world whose picture was already painted by philosophers, priests and professors of law since John Locke, Rousseau and Immanuel Kant. Justice lives only in this transcendental world whose ideals many a society has found itself in pursuit of, ever since. A society is as good and noble as its laws. Not only this, citizens’ sense of patriotism and nationalism towards their country tends to improve when they can trust the law as well as the system that expedites its situational application.

A classic example in recent global memory is found in the Christchurch shooting incident in New Zealand. The culprit, a 29-year-old Brenton Harrison Tarrant, had opened fire at a mosque on March 25, 2019, killing in the process about 51 persons who happened to be Muslims, during a Friday prayer. By August 2020, after Tarrant’s admission to the murder of 51 people, the attempted murder of another 40 people and one charge of terrorism, Judge Cameron Mander sentenced the accused to life imprisonment without any parole. The judgement, coming in less than eighteen months, was the first of its kind in the national history of New Zealand.

Back in Nigeria, the lingering case between the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and a current-serving senator representing the Benue South Senatorial District, Abba Moro, is yet to come to a terminal conclusion since the prosecution entered its case. The senator, who is also a former Minister of Interior, was sued over the botched recruitment exercise that witnessed the death of up to twenty applicants. Consequent upon this incident, he was charged to court by EFCC for criminal involvement in the recruitment process in which his private firm, Dretex Tec Nigeria, was allegedly involved as a proxy frontier in a recruitment scam worth up to N677,000,000. The firm would later be acquitted and discharged by a Nigerian court sitting in the country’s capital, Abuja. In 2019, while the court case yet lasted, the ex-Minister contested and won election that brought him into the Senate. In June 2020, the criminal charges were dismissed by Justice Nnamdi Dimgba on the basis that the EFCC could not establish grounds of fraud that could connect the lawmaker with the alleged offence. While many families linked to the unfortunate fatalities of the recruitment exercise are still reeling from the painful memories of their losses, the now-serving senator presently looks forward to opening his defence on October 29, 2020.

Certainly, these developments will come across as preposterous to much of the global community, especially to nationals of countries where the wheels of justice grind so swiftly that it is taken for granted. But the Nigerian jurisprudential clime is a separate world unto itself. The thesis to this antithetical twist of judicial trends is that, in no distant past, Nigeria had produced notable judges of noble fames, such as Justices Teslim Elias, Karibi Whyte, Kayode Eso, and Justice Isiaka Ishola Oluwa, among other distinguished members of the Nigerian Bench. Indeed, besides the referenced example of the senator, there remains an endless list of judicial cases involving many high-profile murder cases connected to victims that include a former federal Attorney-General, a prominent journalist and a host of political assassinations yet to be unravelled, needless to say determined.

Developments, such as this one, have indeed crystalised into a judicial crisis which sees the perpetuation of a culture of delay of justice, many times leading to the denial of justice for those who truly deserved it. Represented by the Vice President during the Annual Conference of the Nigeria Bar Association that took place in August, the president of Nigeria in his presentation titled ‘Step Forward’ made an open advocacy for speedy dispensation of justice, calling that all criminal trials up to the Supreme Court should not go beyond twelve months, while the prosecution of civil cases should not exceed a period between twelve and fifteen months.

This call, coming from the Buhari government, is one that was already long overdue and reflects the position of thousands, if not millions, of well-meaning Nigerian citizens, majority of whom have suffered systemic and systematic violence in the hands of the Nigerian judicial system. Even the government at national level is not spared of the negative consequences of this menace. The ongoing P&ID saga is a typical case for reference. While the Nigerian society is constantly kept on her toes in unending efforts to sanitize other sectors of the polity, it many times tends to leave out the judiciary. Could this be a matter of natural oversight or a deliberate ‘sacred-cow’ treatment of the judiciary? The maxim that ‘justice delayed is justice denied’ has long been retired into oblivion in the Nigerian legal space since the Lady Justice herself has since, in the Nigerian context, unveiled her visage and wielded the capacity not only to dispense justice, but to identify potential highest bidders among parties brought together in litigation.

In Nigeria, the perceived corruption in the judiciary is both administrative and professional. For instance, Nigerian legal practitioners have a way with ‘technicality’ in their bids to stall justice. The idea in many cases is simply to design a situational process, a series of events in which a legal case is ensured to remain in court for as long as possible, depending on the intension of the higher spender. Lawyers, judges and other ancillary judicial officers form the chain of culpability in this judicial racket. Regardless of a party’s position as plaintiff or defendant, the counsel is, as the practice dictates, expected to be open to the offers of the opposing side in the litigation. An innocent client is often unaware that their counsel is hand in glove with his colleague on the other side, who may receive financial offerings that are paid as ‘settlement’ to judges and all legal and institutional parties connected to the case at hand. From thence, the case takes on a new life as the assigned judge may adjourn or sit as his or her whims dictate.

There is certainly gross inefficiency in the Nigerian judicial system, a stark reality that is signposted by the people who operate the system. It is sheer inefficiency that the Nigerian judiciary cannot dispense with justice in a short time, just as it is a sign of inefficiency that the Nigerian governments, across many political administrations, have a long history of losing legal battles for which it often had all the locus standi, all on account of inefficient prosecution skills or underhanded compromises on the part of those representing the government in cases. Only in few intermittent cases can the country boast of recording legal wins that pass as locus classicus. In a landmark judgement that took place in August 2020, for instance, the Nigerian Supreme Court had vindicated Gladys Ada Ukeje, daughter of deceased Lazarus Ogbonna Ukeje, when it ruled that cultural practices and loric traditions that run contrary to the nation’s constitution by preventing female offspring from sharing in their father’s estate, were at best discriminatory. In the suit referenced as SC 224/2004, the Supreme Court had upheld the position of an Appeal Court establishing that such practices violated section 42(1)(a) and (2) of the 1999 Constitution. But the victory for Gladys did not come until after sixteen long years.

A second legal scenario perhaps is even more critical. First declared wanted in 2013, billionaire kidnap kingpin, Chukwudumeme Onwuamadike, also known as Evans, is yet to have the suit against him, which was opened in 2017, come to a logical legal conclusion, even as of this time. While the accused has been in and out of the courtroom on different occasions, the public is slowly but surely losing memory of any such case involving Evans and six others connected with the alleged kidnap of one Mr. Donatius Dunu, the Chief Executive Officer of Maydon Pharmaceutical Ltd, in Lagos.

Currently, the Nigerian judicial system is both a carcass and shadow of its golden age, a mockery of what justice should be. Far from the ideals of any just society, justice is served in the manner of kebab under an Arabian night. Many lawyers who swore to the oath of professionalism, now offer their time as legal consultants servicing the treasonable interests of powerful enemies of the Nigerian state. Today, many Nigerians who have legitimate cause to go to court for redress are wary of lawyers for the critical reason that a plaintiff is nevermore sure if the counsel whose service is being sought is not himself or herself a potential compromiser of judicial processes. Many lawyers-to-be only wait to graduate from the Nigerian Law School and make straight for this ‘Black Market’ of legal barter.

Read Also: An Antithesis of Justice

The president’s latest call for a more efficient and proactive judicial system is a subtle acknowledgement of a major national crisis. In a nation whose motto is ‘unity and faith, peace and progress’, and which expresses the desire for a country ‘where justice shall rain’, both government and the citizenry must be reminded that, the absence of justice is the precondition for underdevelopment. For a pluralist country like Nigeria, where mutual ethnic suspicion and sectional bickering mar the sociocultural landscape continually, the judiciary has the immediate responsibility of filling the systemic gaps left by years of perceived injustices and lack of equity and fairness. The failure of the judiciary to come to Nigeria’s rescue at such trying times as these leaves the citizenry in the cesspool of obnoxious jurisprudential practices that grounds the country in the perpetuity of legal corruption.

Abiodun Bello